The Art of the Olympics

The Art of the Olympics

When we think of the Olympic Games, the first images that come to mind are of athletes pushing the limits of human performance in disciplines like track and field, swimming, or gymnastics. However, few are aware that from 1912 to 1948, the Olympics also celebrated the human spirit through artistic endeavours. Referred to as the Art Competitions, medals were awarded for works of art inspired by sport, and it was divided into five categories: architecture, literature, music, painting, and sculpture. The Art Competitions were once a cherished part of the Olympic Games, celebrating the intersection of creativity and athleticism.

As we revisit this overlooked chapter of Olympic history, we'll examine how these categories were judged (I mean, art is subjective right?), and take a look at modern efforts to revive this unique category.

The Olympic Art Competitions

The Olympic Art Competitions, also known as the Concours d’Art, were introduced by Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic Games, who was deeply inspired by the classical Greek ideal of a balanced development of mind and body. Coubertin envisioned an Olympics that celebrated both athletic prowess and artistic excellence, believing that the arts should be honoured alongside physical sports. This vision led to the inclusion of art competitions in the 1912 Stockholm Games, marking the beginning of a unique chapter in Olympic history.

Categories and Judging Criteria

The art competitions were divided into five distinct categories: architecture, literature, music, painting, and sculpture [1]. Each category was further subdivided into specific themes, and all entries were required to be inspired by sports, which added a unique thematic constraint to these artistic pursuits. For example, architecture submissions often focused on sports facilities, while literature could include poetry, epics, or dramas centered around athletic themes.

The judging of these competitions was conducted by panels of experts in each respective field, typically composed of well-respected artists, architects, writers, and musicians from the host country and beyond. The criteria for judging were based on both the technical excellence of the work and how effectively it captured the spirit of sport. However, because art is inherently subjective, the judging process was often seen as controversial. There were instances where the subjective nature of art led to disagreements among judges and criticisms from the public.

For example, in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics, the sculptor Walter Winans won a gold medal for his bronze sculpture An American Trotter. However, his victory sparked debate because Winans was also a well-known marksman who had won a gold medal in shooting at the 1908 Olympics, leading some to question the impartiality of the judging.

Walter Winans drew controversy for winning Olympic gold medals in both sport and artistic categories.

Challenges and the End of the Competitions

Despite the initial enthusiasm, the Olympic Art Competitions faced significant challenges, particularly regarding the amateurism rule, which was a cornerstone of the Olympic Games at the time. This rule required that all Olympic competitors, including artists, be amateurs. However, as most professional artists earned their livelihoods through their work, enforcing this rule became increasingly difficult. The line between amateur and professional in the arts was blurred, and many participants in the art competitions were, in fact, well-established professionals.

The issue of professionalism was brought to a head in the 1940s, as the Olympic movement began to modernise and professionalise in response to the growing commercialism of sports. The art competitions, with their complex and often controversial rules regarding amateurism, came under scrutiny. In addition, the logistical challenges of organising and judging art competitions, which were less straightforward than athletic events, further complicated their inclusion in the Games.

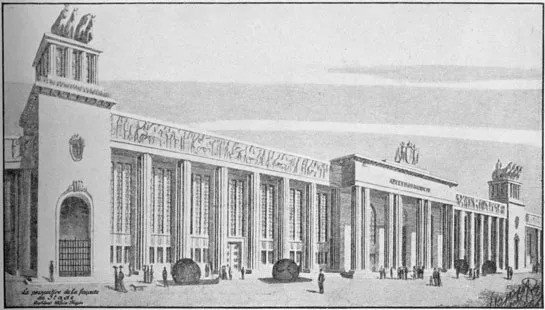

This silver-medal-winning entry at the 1924 Paris Olympics was a palatial structure that could be anything from a museum to a railway station.

It was presented by sportsman and architects Dezsö Lauber (1879–1966) and Alfréd Hajós (1878–1955), both excellent athletes and Olympic medalists, the latter a two time gold medalist swimmer [2].

In 1949, the IOC meeting in Rome received a report indicating that most participants in the art competitions were professionals. As a result, it was recommended that the competitions be discontinued and replaced with an exhibition without awards. This proposal ignited a heated debate within the IOC. By 1951, the IOC had decided to reinstate the art competitions for the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. However, due to time constraints, the competitions were not held, and instead, an art exhibition was organised.

The decision to discontinue the Olympic Art Competitions was made official at the 49th IOC session in 1949, following the 1948 London Games, which marked the last time art medals were awarded. The IOC cited the difficulty in maintaining the amateurism rule as the primary reason for their removal. There was also a growing sentiment within the IOC that the Games should focus solely on athletic competition, reflecting the post-war shift towards a more streamlined and commercially viable Olympic program.

The Legacy and Modern Reflections

Though the art competitions were discontinued, their legacy remains a fascinating aspect of Olympic history, offering a glimpse into a time when the Games sought to unite all forms of human excellence, both physical and intellectual.

In recent years, there have been sporadic efforts to revive the spirit of the Olympic Art Competitions, though none have achieved official Olympic status. For instance, in 2016, Pharrell Williams and the IOC collaborated on an artistic project called Artistic Activations, which invited artists to create works inspired by the Rio Games. While this initiative was not a direct revival of the original competitions, it highlighted the continued interest in integrating art into the Olympic narrative.

Pharrell Williams speaking at an event at the Frank Gehry-designed Louis Vuitton Foundation building to mark the opening of the 2024 Olympics in Paris.

This year, at a high-profile event held on 25 July 2024 at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris, Pharrell Williams proposed reintroducing the Olympic art competitions—last held in 1948—at the 2028 Los Angeles Games. The party was organised by Williams, LVMH chairman and CEO Bernard Arnault, NBCUniversal chairman Brian Roberts, and Anna Wintour. With the coincidence of celebrity influence, backing of big entertainment conglomerates, and the location of the next Games, we think it’s a real possibility, barring some careful renegotiation of the rules and methods for judging.

The Potential for a Modern Revival

If the Olympic Art Competitions were to be revived today, the field could include a diverse array of artists from around the world, both emerging and established. With the evolution of art forms and the rise of digital media, new categories such as digital art, video art, and interactive installations could be included. Artists whose work often intersects with themes of sport and human rights, could be seen as modern-day competitors in such an event.

Art in Modern Olympic Sports

A reintroduction is not really far-fetched concept, we still see a lot of presence of artistry in the Games today. Chief among these is Artistic Gymnastics, where athletes are judged not only on their physical abilities but also on their grace, expression, and creativity. The combination of athletic prowess with the beauty of movement makes Artistic Gymnastics a captivating event, reflecting the Olympic spirit of balancing physical and artistic achievement.

Similarly, sports like Synchronised Swimming (now called Artistic Swimming) and Figure Skating incorporate artistry into their scoring criteria. Athletes in these disciplines perform routines set to music, requiring them to demonstrate rhythm, musicality, and emotional expression, all while executing technically demanding manoeuvres.

A Modern Revival

A modern revival of art competitions in the Olympics feels almost inevitable. The growing recognition of art's cultural and economic value, combined with the increasing intersection of traditional and contemporary forms of expression, makes the reintegration of artistic categories into the Games not just possible, but likely. As society evolves, so too does the understanding that artistic achievement is as worthy of global celebration as athletic prowess.

Art and sport, while seemingly distinct, share a common foundation: both are ultimately about pushing the boundaries of human achievement. Athletes and artists alike dedicate themselves to honing their craft, striving for excellence, and expressing the highest potential of human creativity and physicality. Integrating art into the Olympics would reaffirm this shared spirit, celebrating a more holistic view of human accomplishment.

Beyond the cultural significance, including art in the Olympics offers tangible benefits for the Games themselves. It would attract a broader audience, generate additional media coverage, and create new revenue streams through sponsorships and events. By recognising the relevance of art in today's world, the Olympics could enhance their appeal and solidify their position as a platform that honours all forms of human greatness.

However, reviving Olympic art competitions faces significant challenges, particularly due to the subjective nature of judging art, which resists standardisation. Unlike sports, where performance is measurable, art is open to interpretation, making fair assessment difficult. The potential reintroduction of the amateurism rule adds further uncertainty, as established artists, who often hold significant sway in public opinion, could make judging even more prone to bias. In today's diverse and sometimes polarised cultural landscape, establishing a universally accepted framework for judging art is an increasingly complex task, and one that may be nearly impossible to overcome. Additionally, offering Olympic art competitions today would likely require some inclusion of digital/technological artistic practices to reflect modern creativity. With no precedent for these art forms, it's unclear if the 2028 Games offer enough time to adequately deal with these nuances.

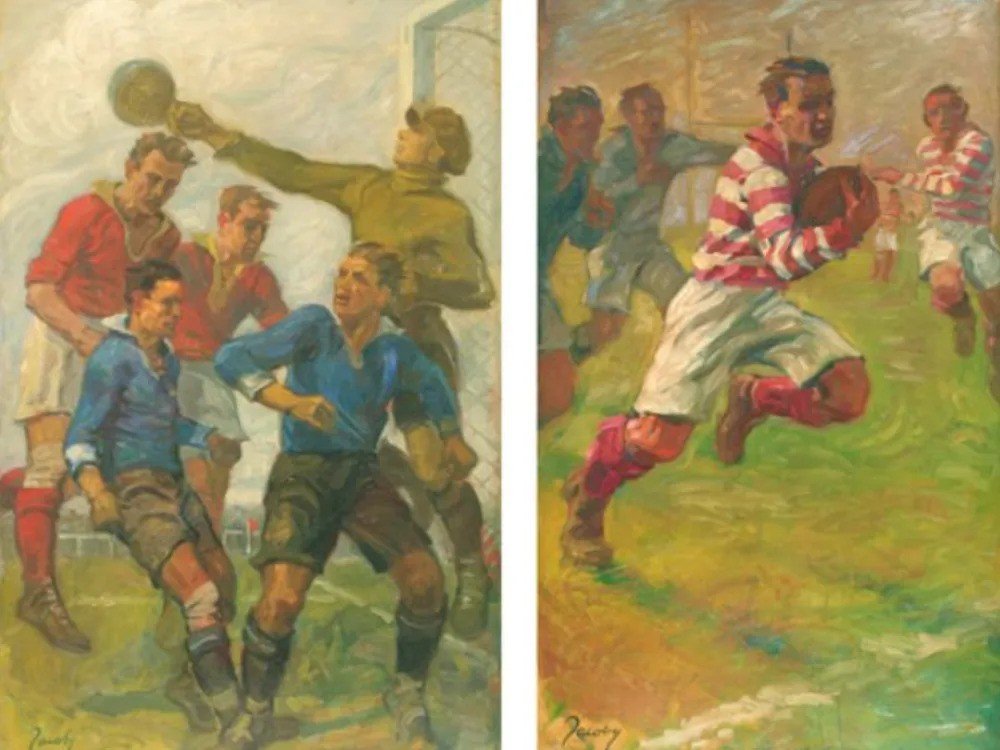

Jean Jacoby's Corner, left, and Rugby.

At the 1928 Olympic Art Competitions in Amsterdam,

Jacoby won a gold medal for Rugby

The Olympic Art Competitions represent a unique chapter in the history of the Games, and we’re curious to see how an attempt at meeting the classical ideal of a balanced mind and body presented by Pierre de Coubertin will look like today. It’s an exciting opportunity to celebrate the full spectrum of human creativity on a global stage, whether through modern adaptations or entirely new formats, the potential for a renewed Olympic celebration of the arts remains as inspiring as ever.

[1] Here’s a more detailed breakdown on the categories:

Architecture: Until the 1928 Amsterdam Games, the Olympic architecture competition was not divided into categories. In 1928, a separate town planning category was introduced. Notable winners include Jan Wils, whose design for the 1928 Olympic Stadium won gold.

Literature: Initially, literature competitions had a single category. By 1928, it was divided into dramatic, epic, and lyric literature. This structure persisted, with changes such as dropping the drama category in 1936. Entries were limited to 20,000 words and required translations or summaries in English and/or French.

Music: Music competitions began with a single category but expanded in 1936 to include orchestral, instrumental, and solo/choral music. By 1948, categories were choral/orchestral, instrumental/chamber, and vocal music. Judging proved challenging, with some years not awarding prizes. Josef Suk won a silver medal in 1932.

Painting: Painting competitions started with a single category, later divided into drawings, graphic arts, and paintings in 1928. Categories evolved over time, with notable artist Jean Jacoby winning two gold medals, the only artist to ever win two Olympic gold medals.

Sculpture: The sculpture category initially included all forms but was split into statues and reliefs/medals in 1928. By 1936, reliefs and medals were separated into distinct categories.

Information extracted from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_competitions_at_the_Summer_Olympics

[2] Sportsman Dezsö Lauber (1879–1966) was a spectacular Hungarian athlete, excelling in everything from cycling to tennis, which accounts for his appearance at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London. So was a fellow Magyar, Alfréd Hajós (1878–1955), a swimmer who won two gold medals at the 1896 games in Athens. Lauber and Hajós also were architects and together presented a plan for a stadium at the 1924 Paris Olympics. The silver-medal-winning entry was a palatial structure that could be anything from a museum to a railway station. A monumental frieze emblazoned its columned façade, and its roofline bristled with rearing horses.

Source: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/olympics-architecture-medals

Written by Milon

Art Again © 2024