SG60: The Story of Singapore's Art Collection

What is it like for a young nation to gather the works that will define it?

Since 1960, Singapore has been answering this question one artwork at a time, assembling not just paintings and sculptures, but fragments of its identity. In a city-state where urban growth and pragmatism have often taken precedence, Singapore’s National Art Collection reveals a richer, more layered narrative. Behind the marble facades and manicured gardens lies a 65-year journey of artistic awakening, one that has grown into Southeast Asia's most ambitious cultural archive.

From Philanthropy to National Memory

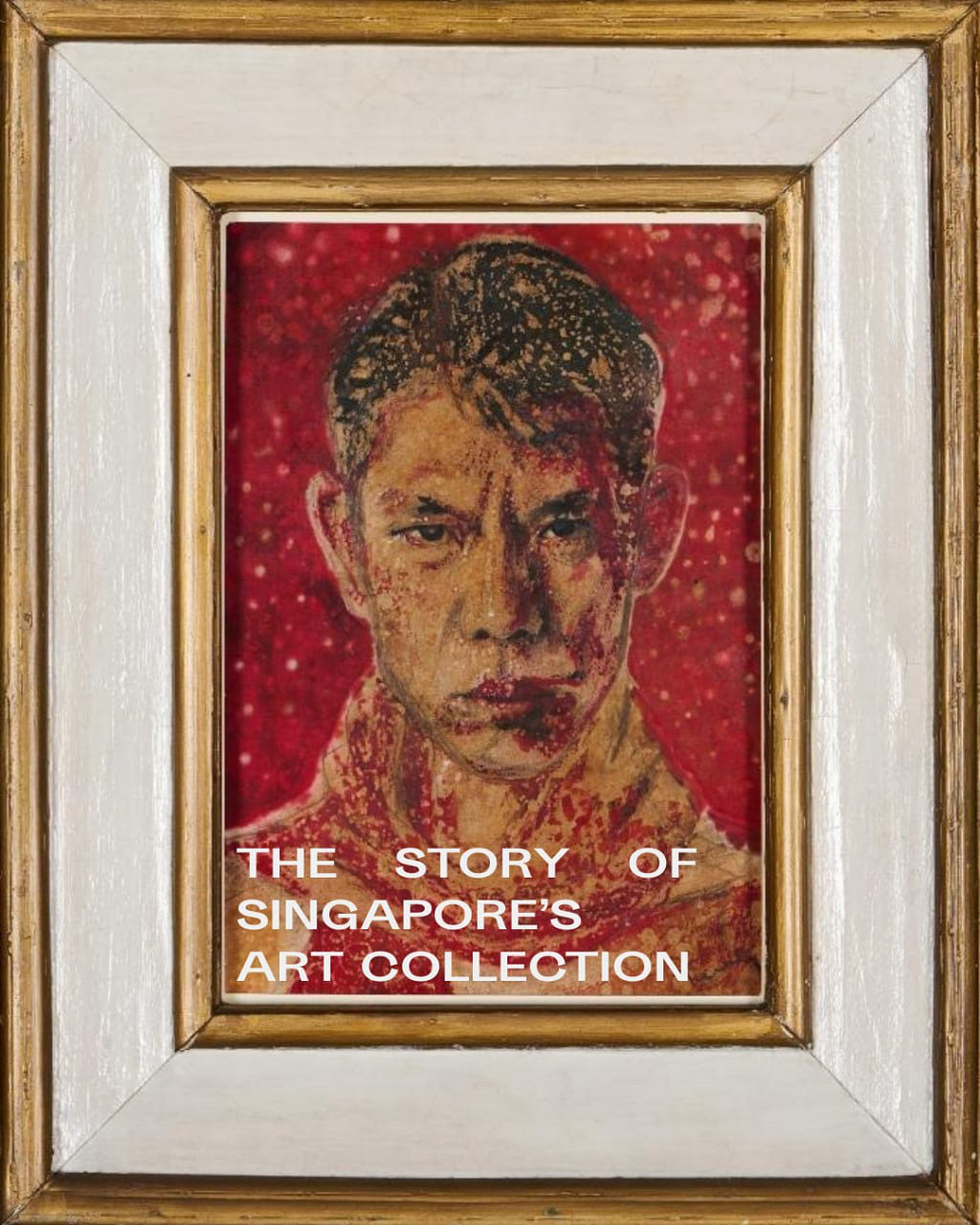

Chuah Thean Teng, Self Portrait, Undated

Singapore's collection journey began in 1960 with one generous act. Dato Loke Wan Tho, a pioneer of Southeast Asian cinema and collector, donated over 110 artworks to the government. Among these was Self-Portrait (1952) by Chuah Thean Teng, the country’s first registered artwork in what became our national visual arts collection. Chuah, often called the “father of batik painting,” elevated a traditional Southeast Asian craft into fine art, perhaps a fitting starting point for our collection.

That seed donation bore fruit with the formation of the National Museum Art Gallery (NMAG) in 1976. NMAG housed modern Singaporean and regional works, planting the institutional roots of our collecting tradition. In 1996, the artworks moved to the Singapore Art Museum, and in 2015 found a majestic home in the restored City Hall and Supreme Court buildings, now the National Gallery Singapore.

Establishing the National Narrative

From the outset, the Gallery had an ambitious aim: to preserve a visual story that resonates not just locally, but across Southeast Asia and the world. Today, its collection boasts over 9,000 works, making it the largest institutional compilation of modern and contemporary Southeast Asian art in the world. This is a collection so huge it has caused controversy with our neighbouring countries.

But it is more than volume. In 2018, the National Gallery kicked off (Re)collect: The Making of Our Art Collection, shedding light on the principles guiding its acquisitions. These include multifaceted values such as artistic, social, cultural, political, historiographical, geographical, and local relevance and international significance, underpinned by accessibility and research potential.

These six principles, outlined by the National Heritage Board (NHB), shape the “National Collection Strategy”. This collective effort links eight key institutions; Asian Civilisations Museum, Peranakan Museum, National Museum, National Gallery, Singapore Art Museum, Indian and Malay Heritage Centres, and the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, to ensure breadth, depth, and coherence across Singapore’s heritage narrative.

What We Choose to Collect

Reflecting multiculturalism and regional ties, the National Art Collection includes two main streams:

-

Singaporean visual art: From early modernists like Georgette Chen, Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Wen Hsi, Liu Kang and Lim Tze Peng to contemporary practitioners exploring themes of hyper-modernity, identity, architecture, alienations, performance and environment.

Georgette Chen,

Family Portrait, 1993

Liu Kang,

Artist and Model, 1954

Cheong Soo Pieng,

At the Market, 1964 -

Southeast Asian art: The collection embraces artists like Indonesia’s Affandi and Raden Saleh; Malaysia’s Latiff Mohidin; Thailand’s Montien Boonma; Vietnam’s Le Pho; Philippines’ Fernando Amorsolo. In a previous blog where we expanded on the two schools of Indonesian Art and their influences, we dissect the very artworks sitting in the National Gallery.

|

Hendra Gunawan, |

Sudjojono, |

Le Pho, |

The scope continues to evolve. Mapping beyond canvas: photography, video, digital and performance art now feature significantly, complemented by historical ephemera, everything from cameras to vintage toys, a gesture towards the cultural everyday.

Policies, Funding & Private Support

Unlike many countries, Singapore has no standalone “Art Collection Act”. Instead, national institutions built collection capability across decades: the creation of the Ministry of Information and the Arts (1990), followed by the National Arts Council (1991), provided the infrastructure and grant frameworks.

In 2013, encouraging steps were taken: the government waived entry fees for citizens entering national museums and committed SGD 62 million to the national collection. Then, in 2024, Deputy Prime Minister Wong announced an additional SGD 100 million in arts funding through 2027 to catalyse creativity and global artistic engagement.

Beyond government grants, private philanthropy plays a vital role. Since 2018, patronage programmes under NHB’s SG Heritage Plan, like the Heritage Patrons initiative and donor-led drives, have funded acquisitions and preservation. In 2018 alone, over SGD 6.5 million was donated by more than 100 patrons. The Gallery’s own Art Adoption & Acquisition Programme counts corporate and foundation partners like UOB, DBS, Lam Soon, BinjaiTree and Yong Hon Kong Foundation among its supporters.

Controversies & Institutional Constraints

Key moments in Singapore’s cultural history reveal a recurring undercurrent — the persistent presence of state influence and censorship of the arts.

Tang Da Wu, Don’t Give Money to the Arts, 1995

-

State-led oversight: A 1994 incident at 5th Passage, an art space, led authorities to freeze funding for performance art until 2004. Sculptor Tang Da Wu’s protest piece Don’t Give Money to the Arts highlighted this tension. NAC has also withdrawn grants for politically or socially sensitive artists such as Sonny Liew, Alfian Sa’at and others whose work challenged state narratives.

-

Curation debates: The Gallery’s mission has been critiqued as overly narrative-driven, privileging nation-branding over artistic complexity. At its opening, some questioned whether curatorial choices smoothed over historical nuance in favour of accessibility and broad appeal.

-

Regional balance: While positioning Singapore firmly within Southeast Asia’s cultural sphere, the Gallery’s framing has raised concerns that a regional lens can sometimes overshadow a distinctly Singaporean voice, folding local narratives into broader regional storylines.

These points of contention continue to circulate among artists, curators and academics, reflecting deeper uncertainties: What is Singaporean art? What makes it Singaporean? For a young, small nation, such questions are inevitable — and there is an underlying fear that the answers may remain elusive for years to come.

Singapore's National Art Collection <> Art Again's "Collection"

Over the past two years of building Art Again, we’ve uncovered many treasures — most by Singaporean artists, some of whom have works housed in the National Art Collection. Here are a handful we'd like to point out this SG60:

-

Wan Soon Kam represents the lyrical documentarian of Singapore's humid tropicality. His "Stream II" (1990), housed in Singtel's collection, exemplifies his mastery of watercolour techniques that breathe with Southeast Asian air. His brushstrokes mirror monsoon rains and the verdant growth that once characterized Singapore and Malaysia.

-

Tay Chee Toh's artistic journey reflects Singapore's evolution from colonial port to technological hub. His "Golden Shadow" (1985), held by the National Gallery, synthesizes nature's organic forms with technology's geometric precision. Working across media from traditional ink paintings to conceptual works, Tay embodies the versatility of Singapore's rapidly changing cultural landscape.

-

Foo Chee San occupied a unique position as both artist and educator. His "Peaceful Village," in the National Gallery collection, captures the rural quiet that once defined much of the island. Foo's paintings preserve the misty stillness and unhurried rhythms that urbanization has largely erased.

-

Lim Tiong Ghee mastered botanical intimacy, transforming Singapore's flora into meditative studies of color and form. His focus on indigenous plant life serves both documentary and celebratory functions, with later works like "Red Hibiscus" demonstrating how artistic maturity can intensify creative fire.

Wan Soon Kam, Stream II, 1990

Tay Chee Toh, Sauce Plate, Terracotta lady and Batik, 1989(1).tif/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.zoom.2048.2048.jpeg)

.tif/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.zoom.2048.2048.jpeg)

Foo Chee San,

Peaceful Village, 1972

Lim Tiong Ghee,

Moonlight, 1995

Found on Art Again

Wan Soon Kam, House On a Knoll, Undated

SGD 3,000

Found on Art Again

SGD 4,000

Tay Chee Toh, Dawn, 2015

Found on Art Again

Foo Chee San, Untitled (Houses in the Landscape), Undated

SGD 3,500

Found on Art Again

Lim Tiong Ghee, Red Hibiscus, 2003

SGD 3,000 -

Peh Eng Seng captured disappearing scenes of Singapore in watercolor. His "Bukit Tinggi," part of Singtel's collection, showcases a different style from the work on our site, both documenting Singapore's vanishing landscapes with distinctive approaches.

-

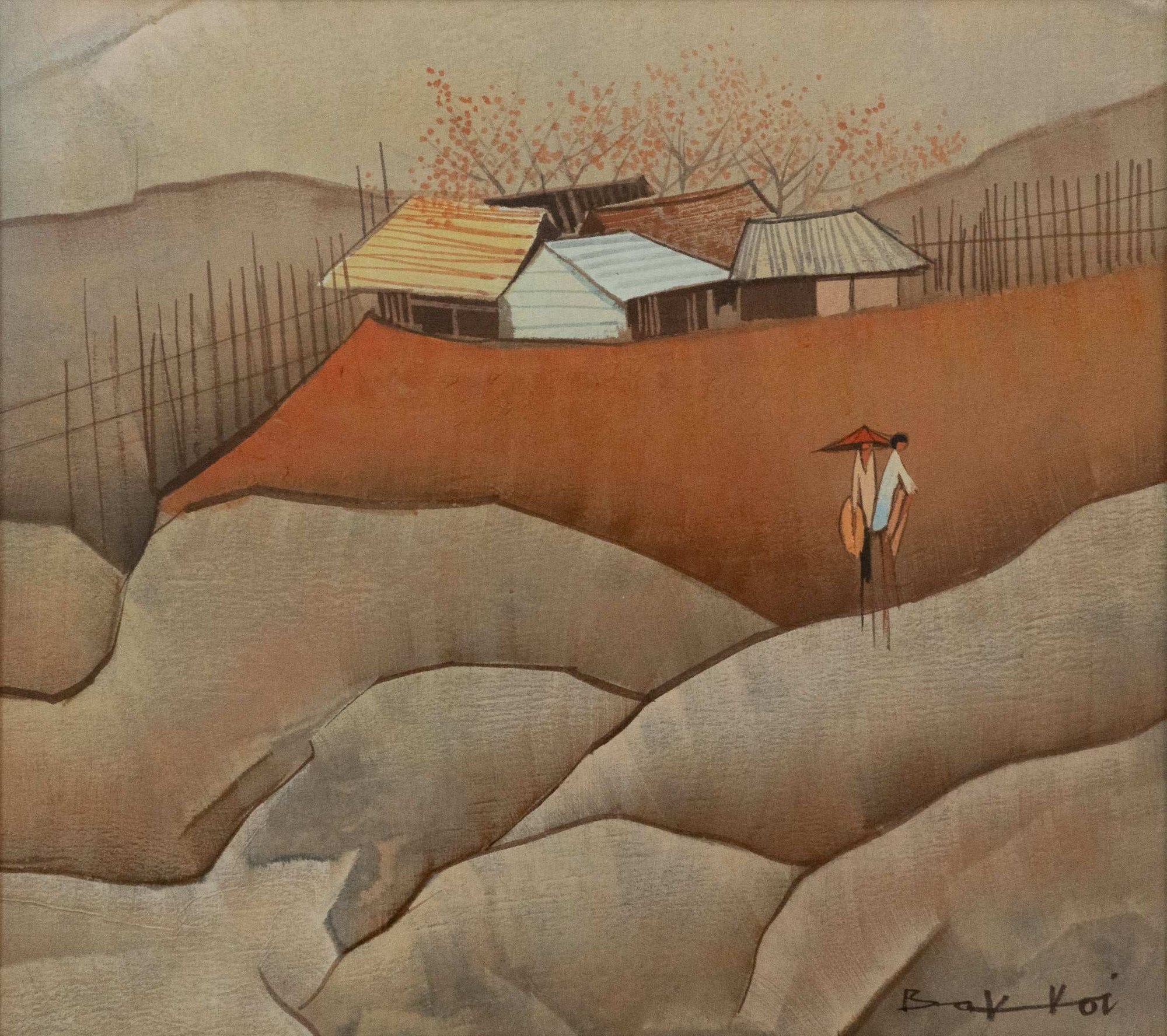

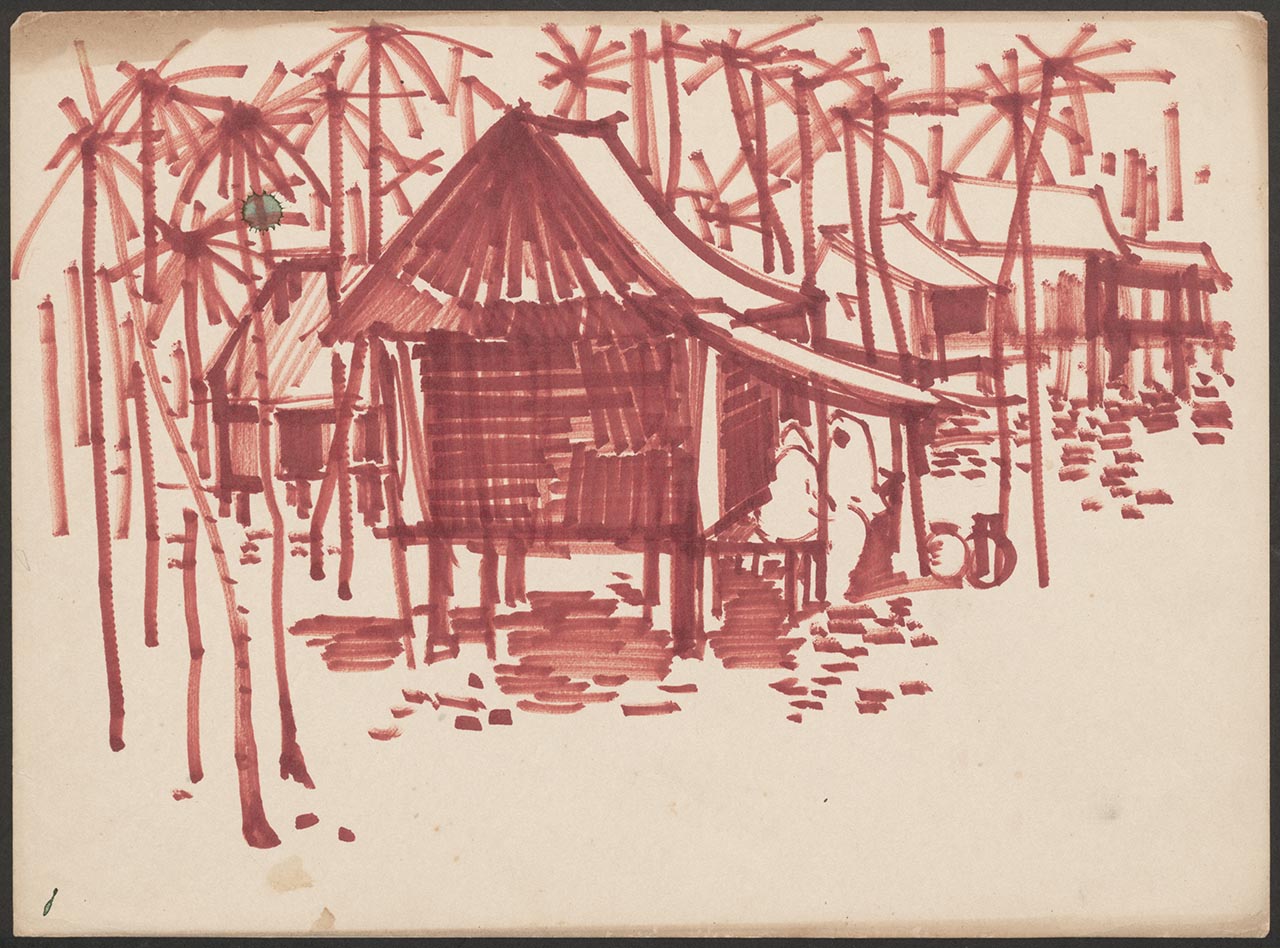

Tay Bak Koi depicted kampong scenes in both his sketches in the National Collection and works featured on our site. His pieces preserve fragments of Singapore's village life, serving as visual records of a disappearing way of life.

-

Jimmy Ong brought extraordinary technical precision to pencil on paper. His large-scale drawings, including "Old Man with Cigarette" in the National Gallery collection, demonstrated that monochromatic media could achieve the same emotional impact as full-color paintings, challenging conventional notions about drawing as secondary art.

Tay Bak Koi, A Sketch, Undated |

|

Jimmy Ong, |

|

Found on Art Again |

Found on Art Again |

Found on Art Again |

These artists collectively represent a crucial bridge in Singapore's artistic evolution. Working in the shadow of the pioneers while facing the pressures of rapid modernisation, they developed distinctive voices that honour tradition while embracing change. Their presence in the National Collection ensures that this pivotal moment in Singapore's cultural development remains visible and accessible, offering insights into how artistic identity forms within the complexities of nation-building.

A National Dialogue

Singapore’s National Art Collection is part of an ongoing national dialogue. Its strength lies in multi-layered collaboration among state bodies, museums, private donors, and the community. Initiatives such as “Collecting Contemporary Singapore,” launched in 2025, encourage citizens to donate play-related items, like Tamagotchis and Hot Wheels, to capture recent cultural phenomena.

Singapore's National Art Collection reveals the choices a nation makes about itself. What to preserve, what to show, who gets remembered. It reflects Singapore’s multiculturalism, regional ties, and the push-and-pull between vision and control.

Six decades post-independence, this SG60 is a moment to reflect on where we’ve been and where we’re going. As we look ahead, the collection’s evolving mandate, to be locally resonant, regionally meaningful, globally relevant, offers a path toward a more comprehensive, honest, and creative Singapore story.

Written by Brenda Chak and Fithriah Hashim

|

If you enjoyed this blogpost, consider buying me a coffee. Please scan the QR code here >>

What is "buy me a coffee"? Buy Me a Coffee is a way for people to tip or say thank you to content creators and creatives.

Also you didn't ask but here're our preferred coffee orders:

|

|

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.1280.1280.jpeg)

(1).tif/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.zoom.2048.2048.jpeg)