SG60: The Singapore River's Many Faces

Still Waters, Shifting Ground: The Singapore River in Art History

The Singapore River has long flowed through the heart of our nation’s collective memory, but in Singapore’s art history, it runs even deeper. Painted, re-painted, critiqued and resisted, the waterway became more than just a subject; it became a symbol. From the 1950s through the 1980s, generations of pre and post-colonial artists returned obsessively to its banks, capturing trade and toil, disappearance and redevelopment, nostalgia and loss. Almost every major Singaporean artist of the era painted it in some form. The bumboats (and their slow disappearance), the working men, the shophouses that remain but no longer hold the same weight or life, they were all captured in the face of exponential change [1].

From a historical standpoint, we all know the story—it’s our collective zeitgeist. The Singapore River was a vital artery of commerce and migration. Bumboats once crisscrossed its waters, thick with trade, as labourers lined the banks, loading and unloading cargo. It was here that Singapore’s early success as a port city took root, an origin story that would lay the foundation for the nation’s greatest transformation. Artists, witnessing this shift in real time, turned to the river as both muse and mirror, recording not just a place, but the evolving anxieties, ideals, and aesthetics of a young nation becoming itself.

An early Liu Kang work from 1959 depicts a bustling pre-independence port. The water, littered with colour, was both a stylistic choice and a reflection, perhaps, of the oil and debris that often floated on its surface. Along the banks, rows upon rows of bumboats with brightly painted roofs sit still, likely captured during a moment of rest. Perspectives are intentionally skewed, and there’s a notable absence of tall buildings along Boat Quay. The work is charming in its most essential sense, because it reminds us of the before.

Masters of the Waterway

On the concrete, artists would sit along the banks with their canvases set up and the searing sun set on them. Each of them looking to capture the waterway, envelop themselves in the scene, and to (quite literally) look for a way to paint something of commercial value, as artists do.

The Singapore Watercolour Society especially loved it. As Goh Sing Hooi [2] described:

"Members of the Society are inclined to paint with realism and local flavour. The Singapore River once played an important role during the days of entrepôt trade. Not only has it economic value, it is also an excellent subject for the artists' drawing board... Alongside the river which bustled with activity, there are shady passageways and a sparkling clean food centre. It is an ideal place for sightseeing and a place where artists gather... By mid-day, the majority would have shuttled back to the riverside..."

|

|

Ong Kim Seng, Singapore River, 1983 This work is available on our site. |

The Singapore River features prominently in many of Ong Kim Seng’s earlier works. We imagine him moving along different stretches of the river over the years, capturing scenes as the landscape evolved. His paintings are often tinted with a distinct orange hue—likely reflecting the harsh Southeast Asian sun overhead, our distinct quality of light and the lack of shelter before the surrounding buildings were constructed. To the modern viewer, that orange now carries a nostalgic weight, much like the warm cast of a sepia-toned photograph.

Singapore’s master of realism, Chua Mia Tee, [3] captured the Singapore River with particular precision. A prolific realist painter, his scenes are easy to imagine as they were, like honest depictions of a river in motion. Yet in his portrayals of the waterway, even his unflinching realism carries a quiet romanticism. The viewer is often first met by the cluster of bumboats in the foreground, water trailing behind them, with makeshift shacks holding their ground in the background. Amidst the cargo and clutter, the water gleams, almost like starlight, imbuing the scene with a kind of understated reverence.

Bumboats appear in nearly every one of these scenes, a recurring subject now absent from our clean, reborn Singapore River. Today, they exist only as tourist vessels, emblazoned with large DBS or UOB logos, stripped of their original purpose. They carry no real weight, not in labour, not in memory.

Chua Mia tee, Singapore River Scene, 1983

Hua Chai Yong's scenes are among the most striking. Painted during the river’s redevelopment, his works are dominated by stark whites—boats, bridges, and buildings appear almost bleached into near-erasure. Colour lingers only in fragments, prompting the question: where did everything go? The answer lies in today’s Boat Quay, where the same bumboats have vanished. Hua's use of negative space intensifies the sense of transformation. Each scene drifts between past and future, nature and steel, clarity and loss, quietly reflecting on the cost of change.

|

Hua Chai Yong, Untitled (Boat Quay, Singapore River), 1981 |

|

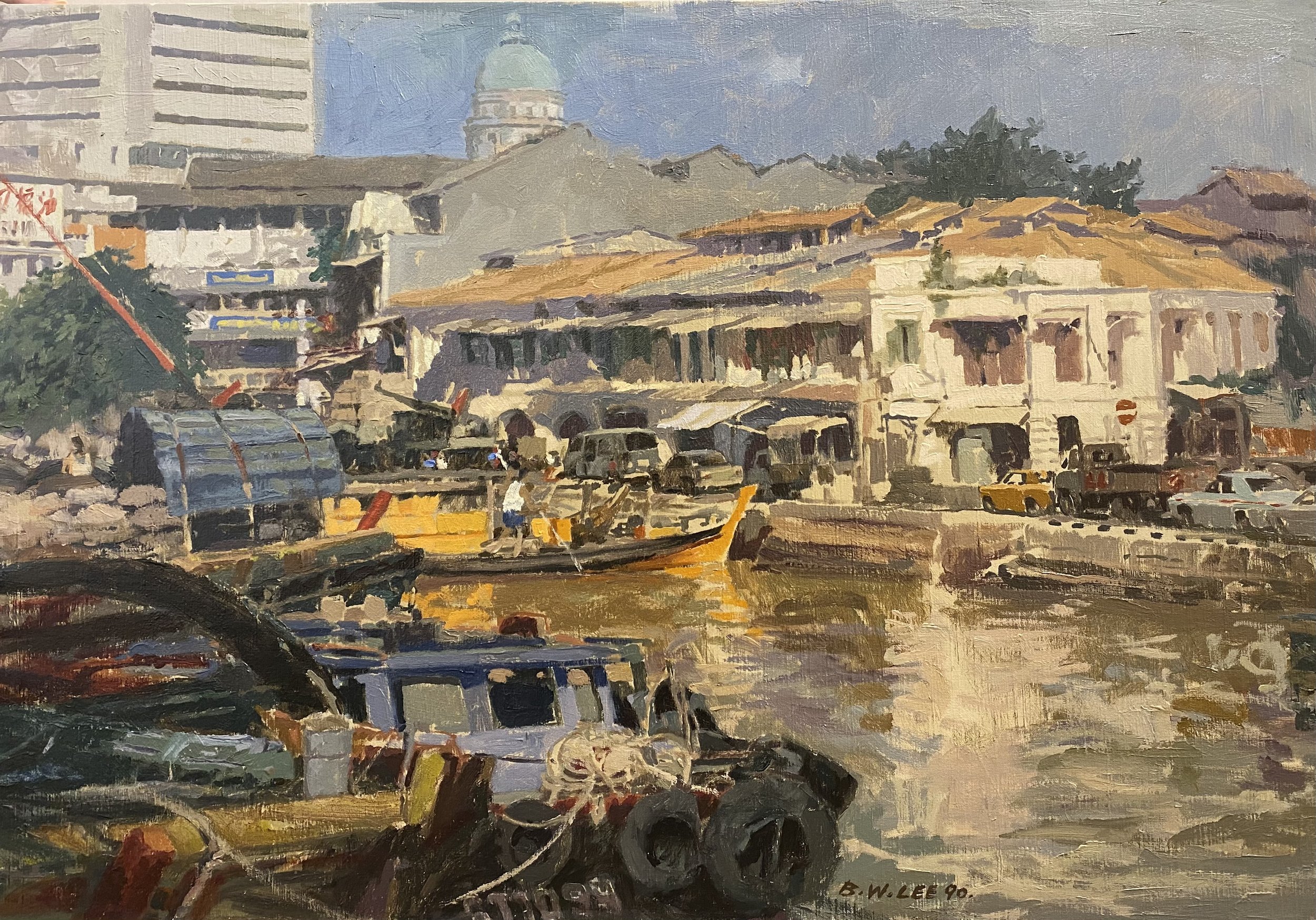

Chen Cheng Mei painted the river simply, in her characteristically charming style. Lee Boon Wang captured it with vivid brushstrokes and rich colour, while Lim Tze Peng used deliberate strokes of Chinese ink. Through these varied artistic approaches, the waterway’s history was preserved, allowing modern viewers to look back and see it as it once was—unfiltered, though perhaps a little romanticised. It was not yet clean, polished, or gleaming under the lights of the Fullerton Hotel and towering skyscrapers. Instead, it was, like any other place, a space where people sought a living.

|

Chen Cheng Mei, Bumboats, 1985 This work is available on our site. |

|

|

In these artists’ depictions of the layers of cargo and the toiling heat endured by workers cleaning the waterway under the nation’s orders, the story of labour is preserved. All of Singapore’s current glamour and sanitised beauty owe their existence to this effort. Yet, just as modern viewers may grow tired of these scenes, contemporaries of these artists started to also express a sense of boredom and unrest.

Charting a new (dis)course

By the 1970s, the repeated and stale depiction of the Singapore River in local art was starting to provoke criticism from within the art community. While the river had long been a powerful symbol and subject, some artists and critics grew concerned about the lack of innovation this fixation encouraged. Among the most vocal was Ho Ho Ying, alongside Liu Kang himself, who challenged the art scene to move beyond familiar motifs and develop a distinct, forward-looking artistic identity. His observations and critiques opened a necessary conversation about originality, commercial influence, and the future direction of Singaporean art.

Though Ho never directly criticised the overuse of Singapore River scenes, he alluded to it in his 1980 essay "Six Undesirable Attributes of the Singapore Art Scene." There, he condemned what he called "The Beehive Syndrome," writing:

"There is a tendency for those painters who do not have a strong character, nor any understanding of art theories, and are unable to establish a personal style in their painting, to suffer from the 'Beehive Syndrome'. These painters are easily seduced by a particular type of work or a special kind of motif and start to imitate it simply because the work will attract a buying audience. Whether it is scenes from Chinatown, the Singapore River, orchids or pigeons, they will paint it as long as there is a market for it." [4]

Though the essay focused on imitation more broadly, there is a clear implication that artists continued to paint the Singapore River out of commercial convenience and conventionality, and this focus, in turn, led to a concerning lack of artistic innovation. Ho was outspoken about the lack of originality in the local art scene. In another essay, "Why Do We Need to Be Innovative," he wrote about Singapore's unique position between East and West and called for a more self-defined artistic identity. He argued:

"As artists, we need to absorb the spirit of modernism. We need courage to establish new concepts, to search for new principles and new methodologies. And this is what we will require if we want to create new forms and new imagery. This should be the quest of our generation. Only when we manage to create something new can a truly Singapore art and a Singapore culture emerge." [5]

Clearly, Ho was all for innovation in the art world. Perhaps surprisingly, in 1974 when Singapore's first conceptual artwork emerged, Cheo Chai Hiang's 5' x 5', a minimalist intervention of four parallel lines incised into the gallery wall and floor—Ho rejected it. In a detailed letter to Cheo, Ho rebutted his proposal and called the work "hollow", "empty" and "monotonous".

Cheo Chai Hiang, 5' x 5' (Inched Deep), 1972

Cheo’s piece was originally intended to be titled Singapore River, perhaps as a critique of the art scene’s obsession with that motif. Naming it this way could have been a deliberate mockery of the local art world’s fixation on the waterway. It may also have been a challenge, questioning why the same subject, presented in a radically different form, was not accepted, suggesting that audiences and institutions valued pictorial familiarity more than artistic experimentation.

'Not the Singapore River'

Of course, as the waterway was majorly painted in the 70s and 80s, this small piece of discourse did not discourage artists. In 1986, however, a (now defunct) private gallery, Arbour Fine Arts, launched an exhibition provocatively titled Not the Singapore River, featuring younger artists like Goh Ee Choo, Oh Chai Hoo, Yeo Siak Goon, Peter Tow and Katherine Ho. Gallery founder Lim Jen Howe told The Sunday Times:

"Not another painting of the Singapore River, please. Or Chinatown in watercolour, or shades of old Singapore. You can't tell one artist from the next because they all use the same theme." [6]

It's interesting to note, though, that in making the entire exhibition antithetical to the Singapore River, gallery owners attracted traction still because of it. The waterway was so pervasive at some point in Singaporean art that even diverging from it meant coming back to it one way or another.

Lim's statement provoked strong reactions from established artists. Ong Kim Seng rebutted with a verbal statement, saying critiques of the art did not have to come at the expense of the heart of Singapore, our waterway.

Teo Eng Seng responded with a work. Recently displayed at the National Gallery, The Net: Most Definitely the Singapore River, was a sculptural installation of netting and "paperdyesculp" forms. Teo's artwork is a declaration that, in light of the Singapore River's social and historical significance, it is important to keep representing it, while also incorporating innovation into the representational medium itself.

Teo Eng Seng's The Net: Most Definitely The Singapore River, 1986

Understanding the Obsession

The reasons why artists of the time were drawn repeatedly to depict the Singapore River, Chinatown, and other familiar scenes are clear to us. Singapore was transforming at an extraordinary pace. While we celebrate this rapid change with pride, seeing it through these artworks reveals the profound cost: not just an abstract loss of eccentricity, but a literal erasure of livelihoods, childhoods, and memories that defined the post-independence era.

Even within the National Gallery, one cannot avoid images of shophouses, Chinatown, and the river itself. Perhaps it was only by capturing these scenes that pioneering artists could hold on to fragments of certainty amid the uncertainty that engulfed them as Singapore and the waterway evolved into what they are today.

To understand why the Singapore River remained such a dominant motif, we must consider its emotional and psychological significance. The river symbolised labour, migration, trade, and survival. For many older artists, it was a daily reality—unpretentious, and raw. It provided a natural anchor to explore light, movement, and mood.

More deeply, the river embodied change itself. Artists returned to the waterway not only to document what existed but also to mourn what was disappearing. The sense of place, the people, and the atmosphere were steadily being replaced by clean walkways and commercial facades. In some paintings, the river is bustling with life; in others, it feels ghostly and vacant. What was once a symbol of working-class grit became a mirror reflecting absence and loss.

In this way, the Singapore River became more than just a subject—it became a vessel for memory, critique, and longing. Even in the late-80s and 90s, critiquing the motif’s overuse, artists communicated a new generation’s ideas, embracing the unknown and bridging past and future. The river, emblematic of constant change, helped artists negotiate Singapore’s evolving identity and speak to universal themes of transformation and continuity.

On a personal note, I find myself profoundly moved by the river motif. It evokes a strange nostalgia for a past I never lived through, a longing for a “good old days” I was never part of. This bittersweet connection speaks to the power of art to bridge time, allowing us to engage emotionally with histories beyond our own experience.

What does the river mean to you? How do you feel when you see it captured in paintings? Let us know in the comments below.

|

If you enjoyed this blogpost, consider buying me a coffee. Please scan the QR code here >>

What is "buy me a coffee"? Buy Me a Coffee is a way for people to tip or say thank you to content creators and creatives.

Also you didn't ask but here're our preferred coffee orders:

|

|