Gutai Art Association: Giving Form to a Postwar Condition

“Lock up these corpses in the graveyard.”

The pivotal Japanese painter and entrepreneur Jirō Yoshihara wrote in the Gutai Art Manifesto. The “corpses” he referred to were the inherited forms and conventions of art that continued unquestioned into postwar Japan. For Yoshihara and the artists who gathered around him, art could no longer rely on tradition or repetition. It had to begin again, grounded in direct engagement with the real, the material, and the present moment.

He continues with a principle that would come to define the Gutai Art Association he founded in 1954:

Gutai Art does not alter matter.

Gutai Art imparts life to matter.

Gutai Art does not distort matter.

Written in 1956, the Gutai Art Manifesto is a text of roughly 1,700 words that articulates the philosophical foundations of a movement emerging in a profoundly altered world, following the devastating war. Yoshihara spends its opening passages dismantling what he calls the art of the “past,” describing it as populated by works that “fraudulently assume appearances other than their own.” His critique is directed less at specific styles than at a broader condition: the persistence of form without urgency, technique without consequence, and symbolism without material engagement.

To the group, Art was not meant to represent something else. It was meant to exist as an encounter, shaped through action, material, and presence.

Postwar Japan and the Conditions for Gutai

The Gutai Art Association was founded in 1954 in Ashiya, near Osaka, at a time when Japan was navigating the layered aftermath of World War II. The country’s cities, infrastructure, and institutions were undergoing reconstruction, while its cultural landscape faced a parallel reckoning. Prewar systems of value; political, social, and aesthetic, had been destabilised, leaving artists to confront fundamental questions about purpose, responsibility, and relevance.

In the visual arts, this moment produced no single consensus. Some artists turned toward revived traditional forms; others embraced imported modes of European and American modernism. Gutai emerged from dissatisfaction with both approaches. To Yoshihara and the artists who gathered around him, neither preservation nor imitation adequately addressed the rupture of the period. What was required was a mode of art that responded directly to lived conditions: material, physical, and temporal.

The term gutai (具体), often translated as “concreteness” or “embodiment,” reflects this orientation. Rather than prioritising representation or symbolism, Gutai artists emphasised presence: the physical existence of materials, the actions performed upon them, and the traces left behind. Meaning was not imposed from outside but generated through encounter.

Yoshihara argues that materials possess their own vitality and expressive capacity. Art, in this framework, occurs when the artist allows matter to exist fully, rather than forcing it into predetermined shapes. This position marked a departure from both academic realism and gestural abstraction as they were commonly practiced at the time.

The manifesto’s emphasis on matter was inseparable from its historical context. In a society reshaped by industrialisation, mechanisation, and the physical scars of war, materials carried weight beyond aesthetics. Paint, paper, wood, metal, electricity, and debris were not neutral substances; they were part of the world Gutai artists inhabited.

Action, Process, and the Role of the Body

Gutai artists approached making as an event unfolding in time. The artwork was understood not solely as an object, but as the outcome of a process, often one that involved the artist’s body directly. In this respect, Gutai anticipated practices that would later be described as performance, action painting, and process-based art.

Kazuo Shiraga is among the most widely recognised figures associated with this approach. Beginning in the mid-1950s, Shiraga suspended himself above canvases using ropes and applied paint with his feet. The resulting works bear the marks of gravity, friction, and momentum, recording the physical conditions under which they were made. Shiraga’s interest lay not in expressive gesture as self-disclosure, but in the tension between bodily force and material resistance.

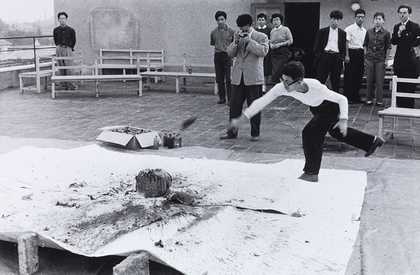

This focus on the body as an active, exertive presence was established earlier in his practice. In Challenging Mud (1955), presented at the first Gutai exhibition, Shiraga leapt and struggled within a pile of wet mud, using his entire body to shape the work. The performance foregrounded effort, resistance, and physical immediacy, and can be understood as a precursor to his later foot paintings, where similar forces were transferred onto the painted surface.

Kazuo Shiraga, Challenging Mud, 1955

Similarly, Saburō Murakami’s Passing Through actions involved running through large sheets of paper stretched across frames. The work existed in the moment of rupture, with the torn paper serving as residue rather than representation. Other artists engaged mud, smoke, water, sound, and industrial materials, each pursuing different modes of encounter.

|

|

|

|

Expanding the Field of Materials

Gutai artists consistently pushed beyond conventional formats. Works extended into space, involved sound or light, and often existed only temporarily.

One of the most well-known examples is Atsuko Tanaka’s Electric Dress from 1956. Composed of coloured light bulbs and wiring worn on the body, the work transformed the artist into a moving structure of light and energy. Other artists used industrial materials, natural elements, or mechanical systems to activate environments rather than create fixed objects.

These experiments anticipated later developments in performance art, installation, and environmental art. Importantly, many Gutai works were not designed for permanence. Ephemerality was not a limitation but a condition, reinforcing the idea that art could be experiential rather than collectible.

Exhibition as Experience

Gutai’s exhibitions reinforced its experimental orientation. Between 1955 and 1957, the group organised a series of Outdoor Art Exhibitions in parks and open spaces, where works were exposed to weather, light, and public encounter. Installations were suspended from trees, stretched across open ground, or activated by wind and movement. These exhibitions challenged the conventions of display that governed museum and gallery settings.

Indoor exhibitions were similarly unconventional. The first Gutai exhibition in Tokyo in 1955 featured installations and actions that emphasised spatial experience and viewer movement. Rather than presenting finished objects for detached contemplation, Gutai invited audiences into situations that unfolded over time.

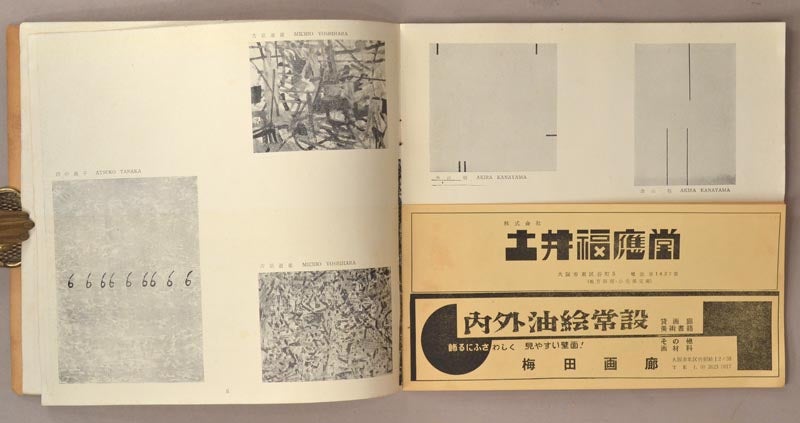

Documentation played a crucial role in this context. Photographs, film, and written accounts preserved traces of works that could not be collected or restaged in conventional terms. The group’s self-published Gutai journal circulated these materials internationally, pairing visual records with essays and statements that articulated the movement’s ideas.

Image from the second publication of the Gutai Journal.

International Exchange and Visibility

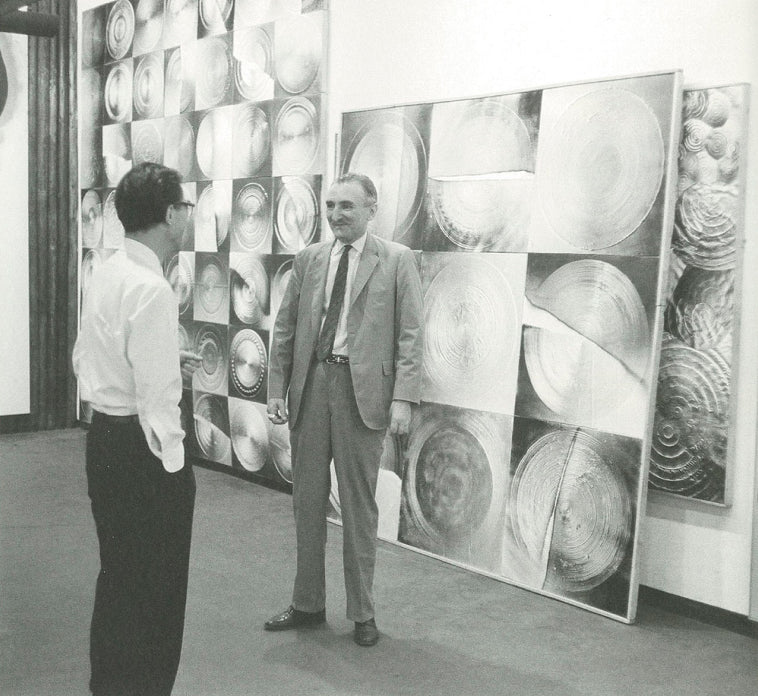

From its early years, Gutai pursued dialogue beyond Japan. Yoshihara maintained correspondence with critics and artists in Europe and the United States, most notably the French critic Michel Tapié, who played a role in introducing Gutai to international audiences. Works by Gutai artists were exhibited abroad from the late 1950s onward, positioning the group within broader postwar debates around abstraction, materiality, and action.

This international orientation was deliberate. Gutai did not frame itself as a national movement or as a representative of Japanese identity. Instead, it sought to contribute to a global rethinking of artistic practice, grounded in shared postwar conditions rather than stylistic affiliation.

Over time, this engagement brought Gutai into contact with artists and movements working in parallel, including Art Informel, early Happenings, and experimental music and performance. These exchanges were uneven and sometimes indirect, but they reinforced Gutai’s sense of operating within a wider field of inquiry.

Michel Tapie at a Gutai exhibition.

Structure, Leadership, and Change

Despite its emphasis on experimentation, Gutai was not without structure. Yoshihara’s role as founder and guiding figure was central. He encouraged risk-taking and originality while maintaining editorial oversight, particularly through exhibitions and publications. This balance shaped the movement’s evolution over nearly two decades.

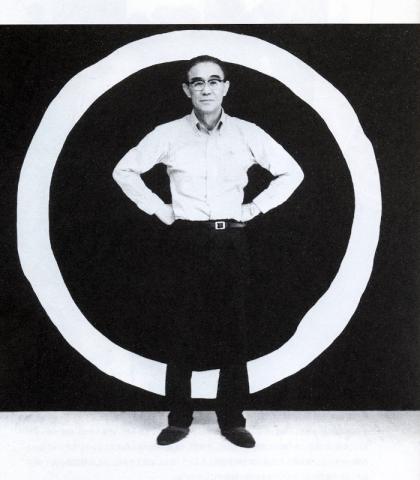

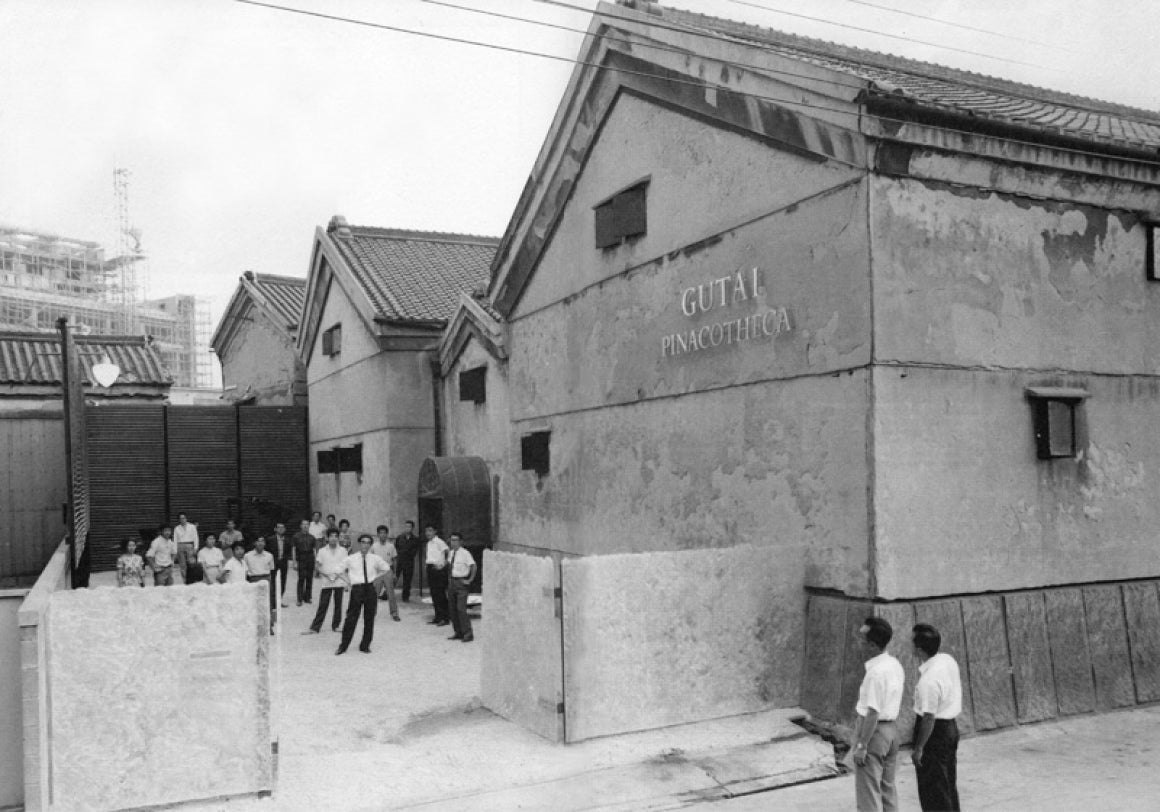

By the early 1960s, Gutai’s activities had become more institutionalised. The establishment of the Gutai Pinacotheca in Osaka provided a permanent space for exhibitions and international exchange. During this period, some works became more materially refined and object-based, reflecting shifts in context and audience.

The Gutai Art Association formally disbanded following Yoshihara’s death in 1972. Many artists continued their practices independently, carrying forward aspects of Gutai’s thinking into new contexts.

The Gutai Group outside of the Gutai Pinacotheca

Keiko Moriuchi and the Continuation of Gutai

Keiko Moriuchi was the final artist to join the Gutai Art Association, and remains the only member personally recruited by Yoshihara himself.

Born in Osaka in 1943, Moriuchi encountered Yoshihara while still a student. At his encouragement, she moved to New York rather than Paris, immersing herself in an international art environment that expanded her perspective.

Moriuchi joined Gutai in 1968, becoming the sole member to be invited by Yoshihara hhimself. She exhibited with the group until its dissolution in 1972. Her early Gutai works often took the form of installations that emphasised repetition, rhythm, and spatial awareness. One such work involved 108 white floor cushions arranged to activate the surrounding space and the viewer’s movement through it.

Her contemporary practice continues to reflect Gutai’s material sensitivity while developing a distinct visual language. Moriuchi’s paintings are built through layered surfaces, often incorporating 24k gold leaf.

In her work, Gold functions as a material associated with illumination and perception, reinforcing the relationship between surface, light, and experience. This approach situates her practice within Gutai’s legacy while extending it into a sustained, individual inquiry.

Keiko Moriuchi, Lu: The Never-Ending Thread I, 2025

This work is available on our site.

Looking forward

Gutai’s significance lies not only in its historical position, but in its enduring questions. How does art remain responsive to its moment. How does it engage material honestly. How does the act of making remain visible within the work itself.

Through Keiko Moriuchi, Gutai is encountered not as a closed chapter, but as a living lineage. Her work reflects the movement’s foundational principles while continuing to test how material, perception, and experience unfold in the present.

Art Again will be exhibiting Keiko Moriuchi in Singapore during Singapore Art Week 2026. Further details will be announced in due course.

Written by

Fithriah Hashim

|

If you enjoyed this blogpost, consider buying me a coffee. Please scan the QR code here >>

What is "buy me a coffee"? Buy Me a Coffee is a way for people to tip or say thank you to content creators and creatives. |

|