Equatorial Light: Rereading Impressionism Through Southeast Asia

Into The Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, National Gallery Singapore’s show presenting Impressionism, opened last week. Since news of the exhibition broke a few months ago, you’ve probably been invited by at least two different friends to see it with them. Featuring impressionist giants like Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and my personal favourite, Toulouse-Lautrec, it’s definitely one of the buzzier shows we’ve had since the previous impressionist show back in 2017. Among seas of exhibitions of great artists with “immersive” (read: Instagrammable) installations, it’s refreshing to have a proper exhibition with the works physically present in our region.

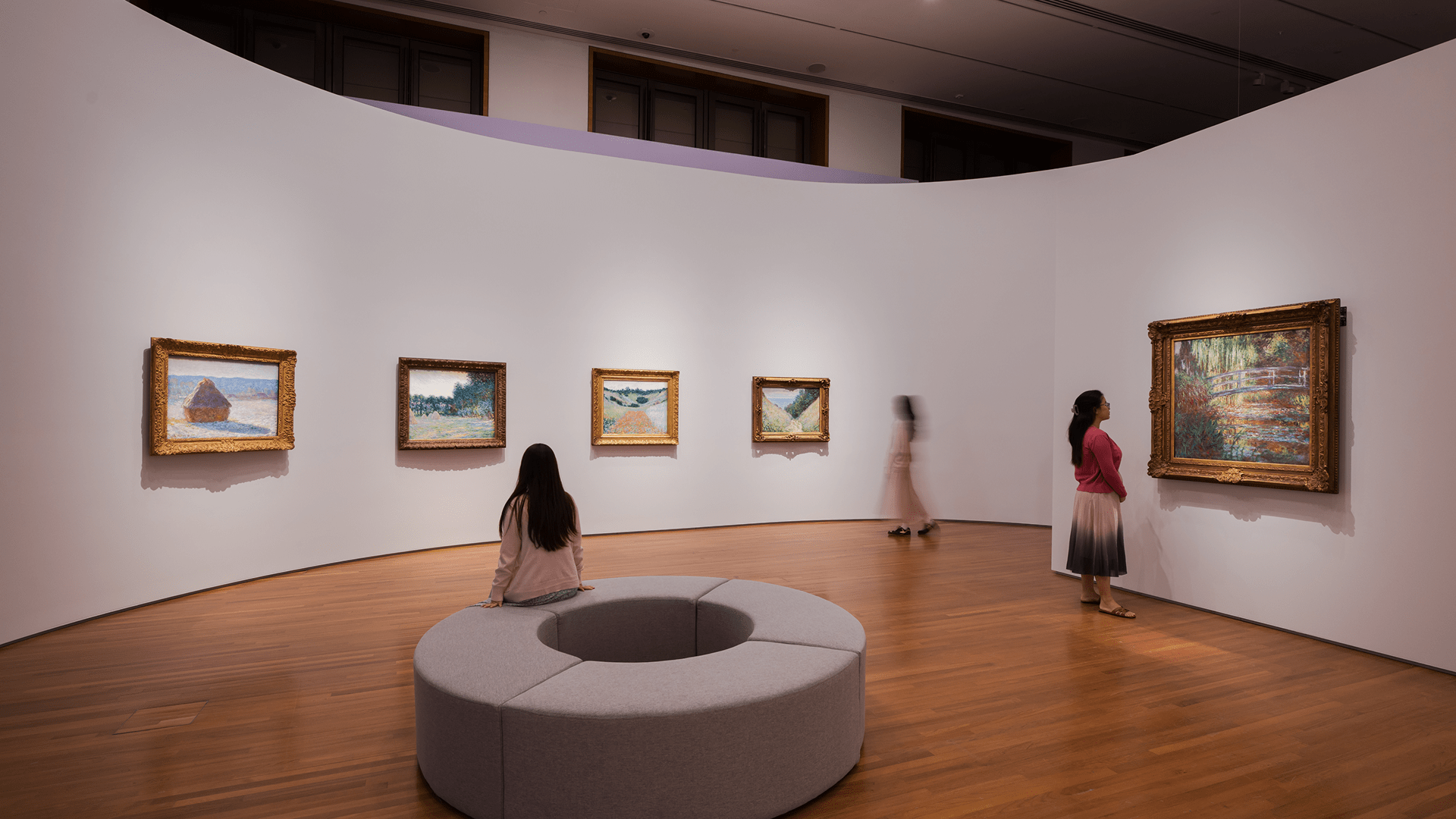

A Section Dedicated to Claude Monet's Works, Part of Into The Modern

Growing up, these painters felt almost mythical next to the Cheong Soo Piengs, Liu Kangs, Sudjojonos and Le Mayeurs I encountered in our own museums. Even in a region saturated with its own modernist brilliance, if you asked someone to name a favourite artist, chances are their answer leaned toward a European Impressionist.

Of course, this wasn’t and should not be a surprise. Beyond the brilliance of the works themselves, the movement quite literally changed the course of art history as we knew it. The rise of Impressionism is immediately related to Expressionism, the rise of Pointillism as an art style, the beginnings of Surrealism, and of course, the abstract depictions of all of the above. These are movements that encompass the likes of Van Gogh, Dali, and Matisse.

Monet's Impression, Sunrise, the work that gave 'Impressionism' it's name.

With the rise of the movement, the landscape of Southeast Asian art evolved, too. Through the influence of the West, the region underwent rapid changes in art history, styles, and what was deemed acceptable in art.

I’ve been waiting too long to see these works in real life, but to me, the arrival of these big-name works also prompts uncomfortable questions: Will regional art history always be treated as second-tier to the West? How do we allow the space for regional artists in our widespread culture when set against the European artists we’ve long mythologised?

Impressionism beyond the artworks

The birth of Impressionism came at a moment when European art was desperate for a shift. For centuries, the only subjects considered worthy of being painted were nobility, deities, or scenes from mythology. Artists were expected to imitate reality as accurately as possible, and the salon system rewarded technical perfection over personal expression. Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia, colonial aesthetics shaped the visual landscape. In Indonesia, the Dutch encouraged the Mooi Indie style, with its picturesque, tourist-driven views of mountains and rice fields. In other parts of the region, local traditions like batik or ink painting were categorised as craft instead of fine art. Artistic value was measured by standards that came from far away.

When Impressionism entered the picture, Europe began to change the rules of painting. Artists stepped outdoors, observed light as it moved across the day, and recorded ordinary people in ordinary places. Brushstrokes became visible, colours were adjusted according to emotion rather than accuracy, and the subject matter expanded to include laundresses, cabaret dancers, city streets and quiet gardens - an expansion that reflected a greater political shift in the region.

Camille Pissarro's Haymaking at Eragny

Monet’s Water Lilies are often treated as a universal reference point for art, which shows how deeply this artistic language has penetrated global culture. The freedom introduced by Impressionism opened the door to Post-Impressionism, Expressionism, and the beginnings of abstraction. The world no longer felt obligated to paint queens and angels over and over again.

Back On Our Shores...

Naturally, Southeast Asia felt the ripple. Many of the region’s early art institutions invited European-trained instructors who carried these new ideas with them. Singapore’s Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) was shaped by artists who believed that studying outdoors and observing local subjects was essential. Indonesia’s art schools, particularly in Bandung and Yogyakarta, absorbed modernist techniques brought in from abroad. At the same time, young artists from the region were travelling to Paris and Shanghai and London, seeing the modernist boom in real time and bringing that experience back home. The result was a version of modern art that was deeply informed by the West but rooted in local texture, colour and atmosphere.

Georgette Chen, Durians and Mangosteens, 1965

Artists like Georgette Chen painted brightly coloured still lifes and luminous portraits carried clear Post-Impressionist influences. Her compositions held the softness of impressionist light but reflected the environment she lived in. The fruits she painted were tropical, the people were from her community, and the rhythm of her brushwork responded to the world around her instead of the salons of France.

Liu Kang also stood at this crossroads of influence. His time in Paris shaped his sense of form and colour, and his later travels across Southeast Asia helped him translate those ideas into the warm, saturated hues that characterise the Nanyang style. His paintings of Bali and Malaya carried the spirit of Cézanne and Matisse but spoke in a language that belonged to the region.

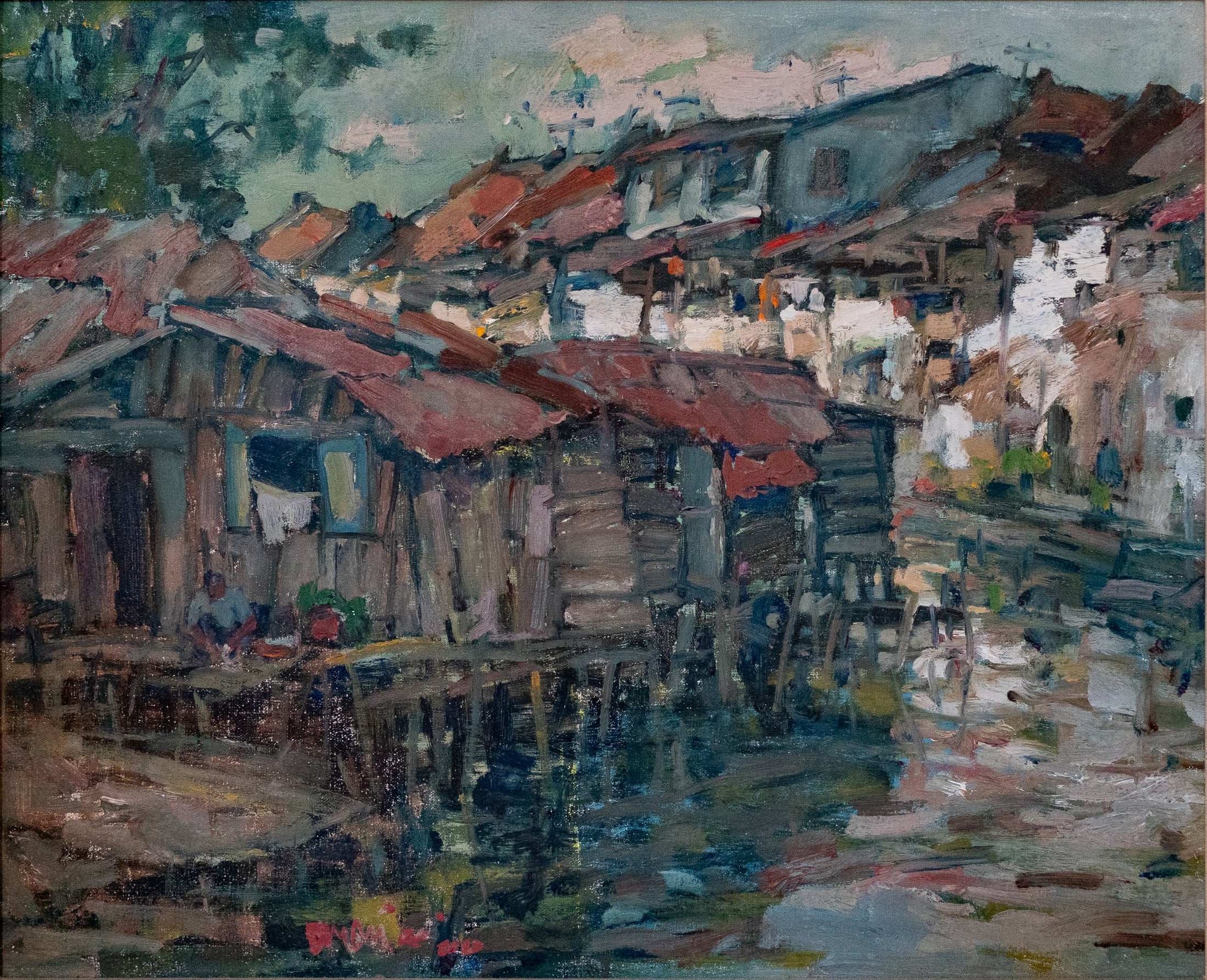

Tan Choh tee, Untitled (Houses on Stilts), 2000

Other artists deepened this connection. Lim Hak Tai, the founder of NAFA, believed that Southeast Asian art should carry its own identity even while learning from global movements. Lai Foong Moi, who studied in Paris, returned with a palette that seemed to glow from within. Her portraits and landscapes blended the softness of impressionist colour with the clarity of tropical light. Tan Choh Tee, known for his textured scenes of Singapore streets, embodied the way later generations inherited modernist techniques and made them local. Wu Guanzhong pushed the dialogue even further by blending the structure of Post-Impressionism with the sensibilities of Chinese ink painting. His belief that form and feeling could coexist created a visual vocabulary that influenced an entire generation of Asian modern artists.

The Philippines saw its own version of this development. Painters like Federico Aguilar Alcuaz experimented with impressionist colour and post-impressionist composition, weaving together European influences with the particular energy of Manila. Ibarra dela Rosa and Norma Belleza carried forward the same spirit, creating paintings that felt both familiar to Western-trained eyes and unmistakably rooted in their own culture. The result was a regional modernism that did not imitate Europe but responded to it in ways that were specific to place and history.

Ibarra Dela Rossa, Park Trail, 1971

Impressionism In The Context of Southeast Asia

When Impressionism reached Southeast Asia, it did not arrive as a neat stylistic package to be copied. The artists who encountered it were working in a climate and geography entirely unlike the ones that shaped Monet or Renoir.

Early modernists in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines were contending with social, cultural, and environmental realities that Western artists were not confronted with. Liu Kang may have been fascinated by the freedom and looseness of Impressionist brushwork, yet his scenes of Bali carry an intensity that refuses the delicacy of the French masters. Cheong Soo Pieng’s compositions stretch and exaggerate the human figure in ways that reflect local sensibilities rather than European ideals. Sudjojono saw Impressionist techniques as tools that could illuminate the spirit and struggle of the Indonesian people. These were not passive adaptations. They were creative recalibrations rooted in lived experience.

Sudjojono, Perusing a Poster, 1956

If anything, what took place in the region was a profound test of whether an imported movement could survive outside its birthplace. It survived because Southeast Asian artists treated Impressionism as a starting point rather than a ceiling. They took the looseness of the brush and applied it to markets, kampongs, riverbanks, and volcanic landscapes. They painted people who looked like the world around them and scenes that carried the weight of cultural memory. In doing so, they gave the movement a second life and expanded its vocabulary in ways the original painters never imagined.

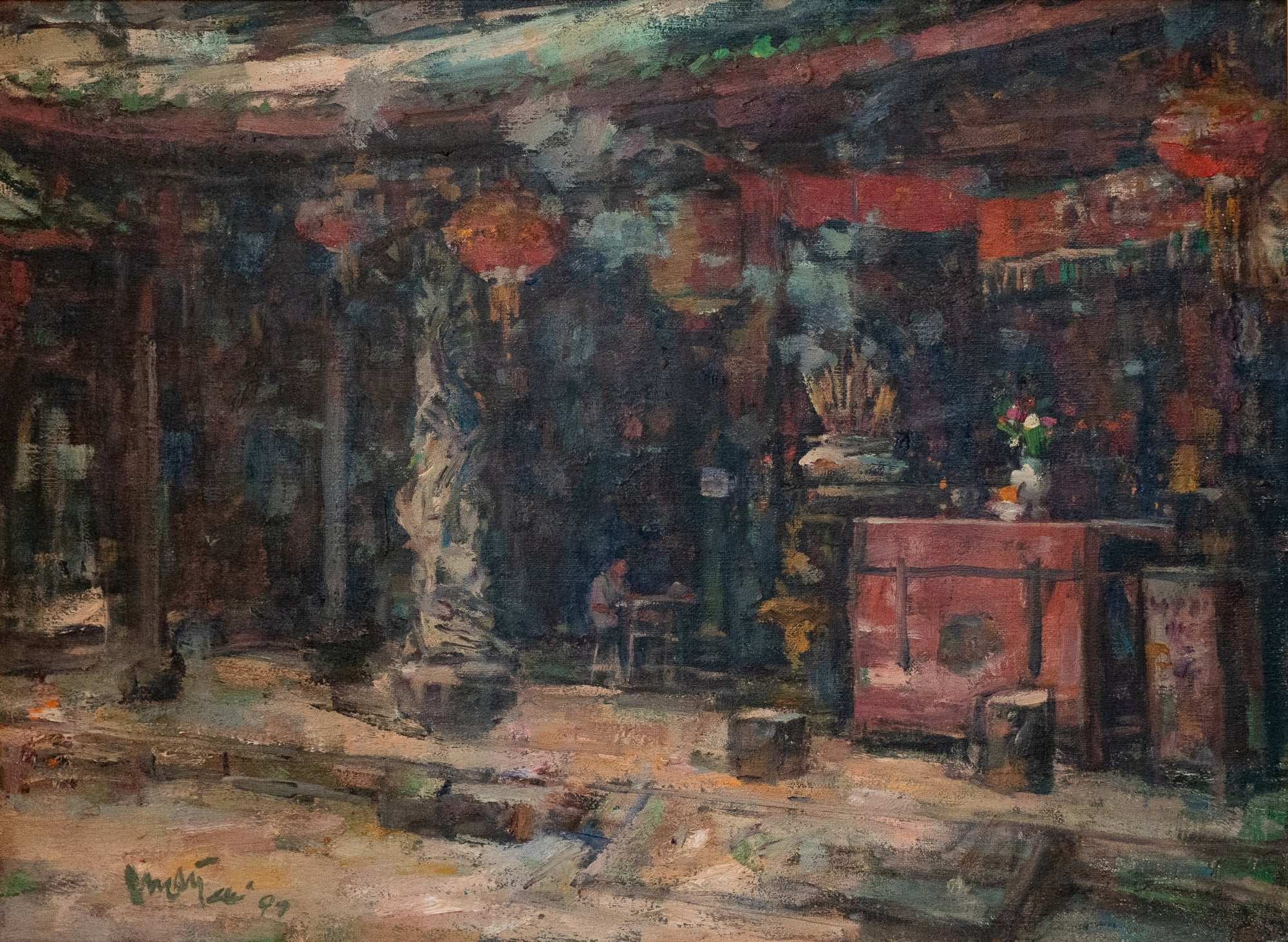

Tan Choh Tee, Thian Hock Keng Temple, 1997

The Ongoing Dialogue

This raises the question at the centre of this reflection: why do we continue to speak about Southeast Asian modernists as if they stand in the shadows of their European counterparts? If they transformed a global movement with such authority, why are they still introduced with disclaimers and qualifiers? We know the usual reasons. Western art histories dominated global institutions for decades and shaped taste, scholarship, and the market. Yet the work itself tells a different story. The paintings produced in this region show a level of innovation that challenges the assumption that influence flows in a single direction.

Teng Nee Cheong, Still Life with Mangoes and Durians, 1970

Tropical environments reshaped Impressionism into something altogether new. Cultural contexts deepened its emotional range. Artists here wove social realities into colour and atmosphere with a directness the French masters were never confronted with. These qualities are not evidence of a secondary lineage. They are markers of an art historical trajectory that deserves to be studied on equal footing with any European canon. If anything, Southeast Asian modernism demonstrates how global movements evolve through encounter and reinvention.

So when we stand in front of a Monet or a Cezanne in the National Gallery today, the experience is meaningful not because these works are inherently superior, but because they help us understand the conversation our own artists entered into. These imported masterpieces remind us that Impressionism travelled, transformed, and eventually rooted itself here. What emerged in the region was not a footnote. It was a parallel modernity shaped by tropical light, complex histories, and artists who refused to be mere spectators of global change.

To view Southeast Asian art as second-tier is to ignore the ways it expanded the possibilities of modernism. I'd like to ask how we can shift the conversation culturally, and begin treating our regional greats as foundational than supplementary to the greats of Europe.

|

|

|

Written by

Fithriah Hashim

|

If you enjoyed this blogpost, consider buying me a coffee. Please scan the QR code here >>

What is "buy me a coffee"? Buy Me a Coffee is a way for people to tip or say thank you to content creators and creatives.

Also you didn't ask but here're our preferred coffee orders:

|

|